Part II: Preparing for Takeoff

The flight to the edge of space was just days away. The grandiosity and magnitude of it all were becoming more potent by the day, and I could hardly believe what I was preparing for. My team and I did one final gear check and headed out to Beale Air Force Base for the following week. With hundreds of phone calls and emails behind us, we knew we had done everything possible to make the shoot successful. Now was the time to bring it to life.

Upon arrival at the base, I went through an extensive physical with the flight doctor. I knew that any single issue could cause a delay or cancellation of the project, and having worked and perfected every detail for the last eight months, there was some serious pressure involved. Even things like minor colds could disqualify someone from going on a flight. There had even been issues where a toothache resulted in the near loss of consciousness because of the pressures at high altitudes. Fortunately, I had somehow avoided getting the cold going around my kid’s school at the time, and I was in excellent physical, mental, and dental shape.

In the first hour of being on the base, I realized how significant this was. The gravity of what was unfolding before me really started to sink in, and there was an electric feeling in the air. Everyone I met was thrilled to be a part of a civilian high flight—this hadn’t happened in several years. Even my doctor talked to me about photography as much as my physical shape. After an hour and a half of checkups, I received clearance for a high flight.

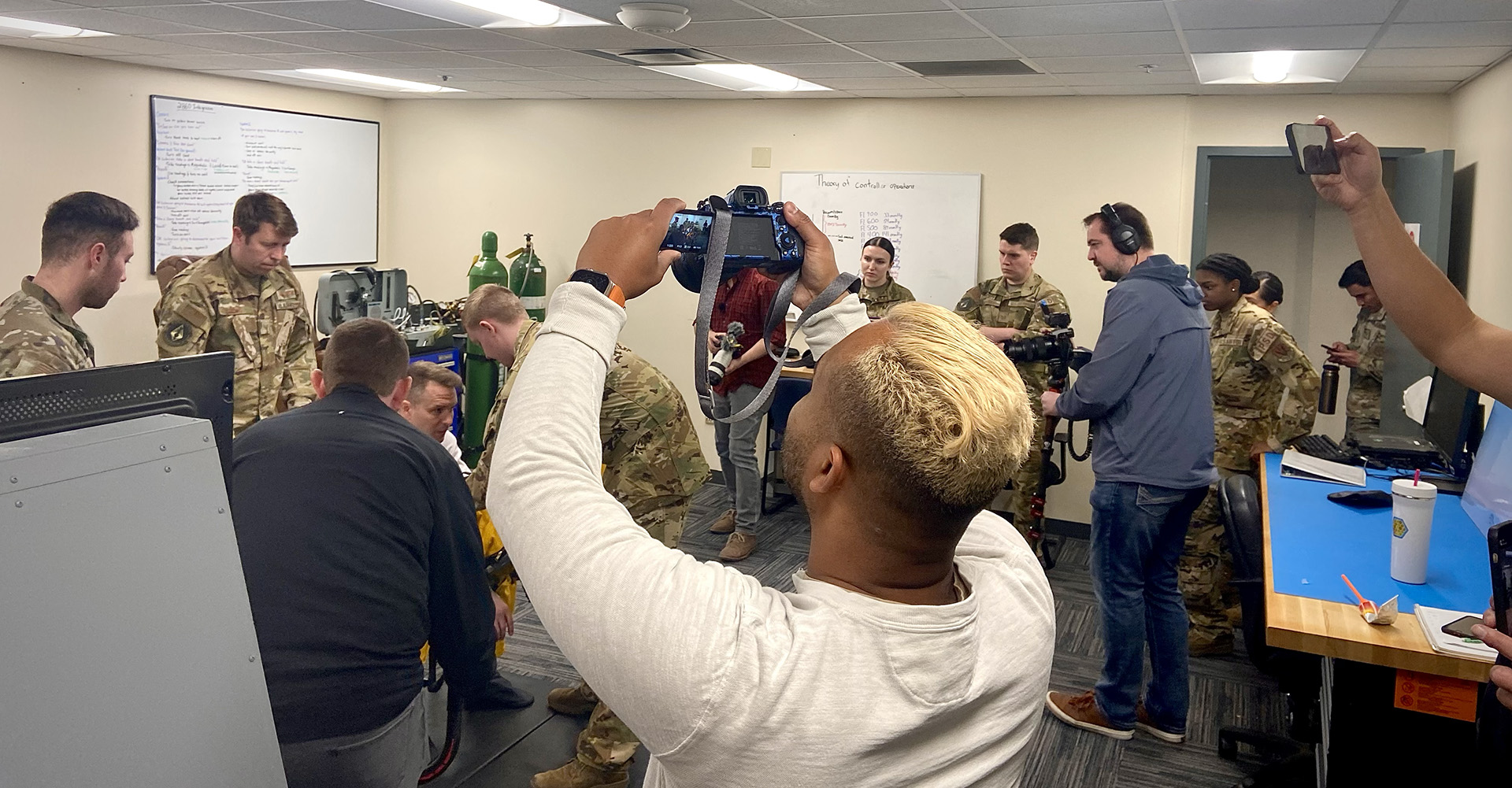

I walked out of the doctor’s office to cameras surrounding me at every angle. Camera crews had arrived to document the mission, and being the one who is usually behind the lens, I felt an unusual twinge of self-consciousness. This time, I was the one in front of the camera. This was just one of the many moments where reality hit me with an unfamiliar force. In all my career experiences, never had I anticipated one like this.

Next up was survival training. I had done this kind of training in the past for my F-16 flights and with privately-owned fighter jets. It is always a grounding situation that causes serious reflection upon the task at hand when one goes through it. However, for the U-2 flight, the reality of its severity was at another level, and I found myself mentally having to take a step back on several occasions to tell myself it was all going to be OK. It was hard for me to remember what parachute lines to cut if we had to eject, let alone knowing how to stay calm and conserve my air if it happened. Once you hit a certain altitude, there are entire minutes of falling before reaching a level at which a human can breathe. There were a couple of moments at which I had to stop the presentation and say that if these potential situations were to occur, maybe I just wasn’t meant to make it. It was a morose kind of levity that afforded me a smile and laugh, as if a defense mechanism blocked my ability to fully recognize the situation.

We moved on to egress training, which is where I learned how to eject and which situations would require pulling specific handles, whether for oxygen or punching out of the plane completely. Thankfully, this session was a bit of a shift from the stress and anxiety of all the training, as the pilot that briefed me on this was hilarious. Even with the reality of what we were talking about, we joked and laughed nonstop. At this point, however, I asked the camera crews to limit their amount of coverage; though there were moments of comradery and team building throughout the whole process, there’s only so much background footage that people want to see, as most of the preparation phases were incredibly stressful.

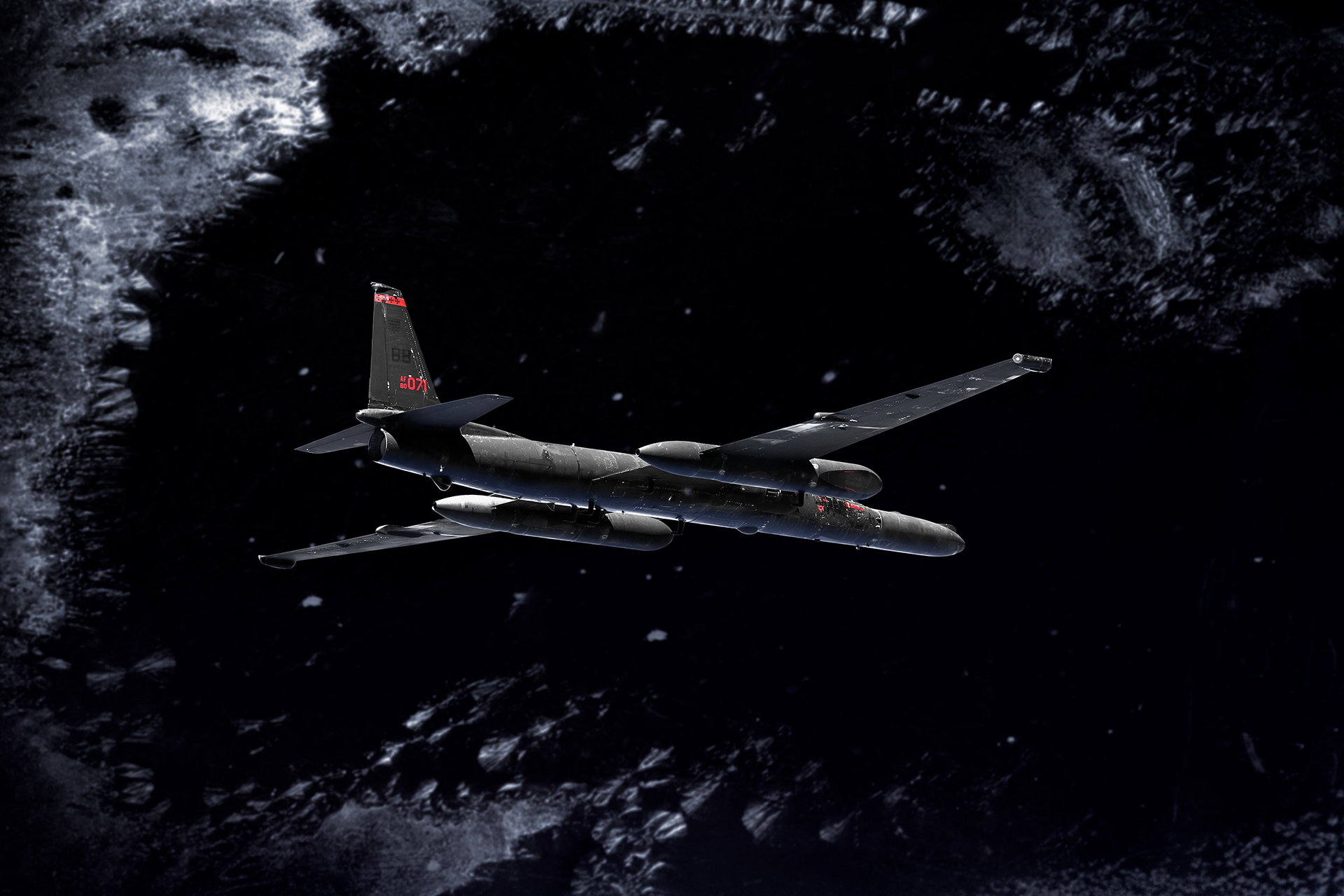

Once we wrapped the briefing, we struck out to the hangar, where the jet waited in all its black and terrifying beauty. The last time I’d seen the U-2 in person was during my tour of the aircraft a number of months prior, to see what might be achievable with the photoshoot. This time was different. I wasn’t there to wonder what would be possible, but instead was there to set up the cockpit for the flight just two days later.

Maybe it was a mental game, but the cockpit seemed to have shrunk since the last time I sat in it. The U-2 cockpit makes an F-16’s look like a house. Due to the pressurization and necessity to keep the weight of the plane as low as possible, the U-2 cockpit can be downright claustrophobic, if the spacesuit wasn’t already enough. One thing that helped immensely during all this was the positivity from everyone involved, both from the base and my team. Their kindness, genuine care, and fierce belief in my capabilities made me feel as confident as I could have been in this situation. I knew it was a pipe dream to bring three cameras for the flight, but never once did anyone say it was impossible. Instead, we all worked together to make a way.

That evening, my wife flew in from California, which meant everything to me. She is my rock and can always help me focus even under serious amounts of stress. The need for her mental fortitude was never more evident than when I woke up at 3 AM, convinced I didn’t have what it took to do the project and shaking with fear. I’m not ashamed to admit that I was absolutely terrified, but her presence alone was such an unparalleled source of comfort and strength, and I couldn’t have done it without her.

Though I’d hardly slept the night before, we returned to the base with an excitement and energy that woke me up more than coffee could. Everyone at Beale worked to their utmost ability to make this expedition as seamless as possible, and I will forever be grateful to them for this. I did my morning briefing with the suit integration squad and with my wife sitting next to me. I was awe-struck listening to the amount of engineering that went into the suit and how prioritized survival was. Though we were discussing the gravity of danger that lay ahead of us, I knew I was in good hands, and I started to genuinely smile again. After the briefing, it was time for me to be integrated into my suit so that I could go into the pressure chamber and start testing.

I thought about the last time I was at the base with my best friend, and how back then, it was just me and him and those responsible for getting me suited up. Upon walking into the room this time, however, a swarm of cameras and media flooded every inch of the space; it was a staggering amount of attention that should have increased my anxiety, but instead, something clicked. Suddenly, I wasn’t afraid anymore.

Moving forward in my training, I was put into a plane simulator and made hypoxic, which means to have my oxygen reduced to where I started losing lucidity. The reason for this is that they needed me to identify what happens to my body when my brain starts losing oxygen so that if it happened during the flight, I could recognize it. For some people, this results in an extreme feeling of happiness, but for others, it is a lethargic reaction. I could tell that my fingers tingled, and the rear right side of my head started to get a mild headache. It doesn’t sound like much, but I knew what to look for and what to do if the symptoms were to reappear during the flight. After this, we cleared the room briefly so I could begin the suit integration. (Going to the edge of space requires one to have a catheter, which wasn’t something I wanted to show the cameras… you’re welcome.)

Once the initial layer of the spacesuit was on, we invited the cameras to return to the room, and the team from Beale walked me step-by-step through the process of what they were doing and why. After getting fully suited, I sat in what felt like an oversized La-Z-Boy chair, and they hooked me up to several tubes and machines. Some were responsible for the inhale and exhale portion of the helmet, some for the suit’s pressurization, and others for the communications with the person wearing the headset next to me.

Somehow during all of this, I began to truly relax. Peace washed over me in the care and direction of the team, and it became easy for me to practice deep breaths. During the integration, I had to inhale multiple times and hold it so that they could read numbers relating to the oxygen and its movement in the suit. I was also handed a clipboard with different types of space food I could eat while on the flight. It was a surreal experience, just like everything else involved with this project, but I remember chuckling as I ordered four chunky apple pies and three bottles of grape Powerade. It was the little things like this that made up for all the stress of preparation and training.

Once the tests were finished, the team from Beale sat me up in the chair and we headed over to the pressure chamber. Over the next hour, we would go through a regiment involving how to eat, drink, and urinate while in the plane. I would need to adapt my ear and sinus pressures to the elevation quickly, and without touching my face. They even let my wife put on a set of headphones, and she and I joked back and forth on what we would tell my daughter about all this. At one point during a helmet check, I looked up to see that they had given my wife a tube of chunky apple pie, to which she agreed with me that it was indeed amazing.

From there, we wrapped early to prioritize my rest before the day of the flight and collect my thoughts going into it. I ate dinner with my wife and friends—a meal of bland chicken and rice that had been determined for many months prior. The idea behind this pre-specified diet was to have food that would be as close to my regular diet as possible without causing any gastrointestinal issues. Somehow, to my amazement, I got a full eight hours of sleep that night. What came next would be the biggest event of my career. It was time to create some history.