Firstly, I want to thank those that sent over emails or messaged me on FB and Twitter about the new ASU campaign. It was a ton of fun to produce, and when my readers enjoy the shots, it is icing on the cake.

As happens a lot, many of the emails had the age old question, “how did you light it?” buried in there somewhere (often thinly veiled as an “oh, BTW”). So today I thought I would take a bit of time to talk about that, some lighting theory and show some RAW files from that and other shoots because I think this sort of thing needs to happen more often.

To be honest, this idea has been in the making for some time now. I have had the good fortune of meeting with quite a few agencies lately and have begun to see two very distinct approaches to photography emerging. The first approach contains a lot of lighting and a technical appreciation of what a purist would consider painting with light. The second one concerns me, it is an approach that more or less says flat light everything and …. (my most despised line) “fix it in post.”

I enjoy the approach of fixing things in post as much as I love listening to heavily auto-tuned music. Then again, for me auto-tune might make my singing voice a bit more angelic, but I digress…

Today I want to talk about a return to lighting because our clients deserve it, our medium deserves it, and we deserve it. Now there will always be things that can’t be done in camera, perhaps due to a location that makes it impossible to travel the subject to, or an action that endangers the subject or crew, and for this there will always be comping, and for those reasons there is nothing wrong with that approach.

So let’s talk about lighting, specifically for mood.

The first place that I went to develop my approach towards lighting theory was not a photo book, but rather my psychology courses in college. It was a common theme that as humans we feel comfortable when we know what is around or in front of us. A quick Shark Week analogy… I went for a swim last Saturday during the day. It was at my neighbor’s house, the pool was clear, I knew what existed because I could see it. Now put me in that same pool at night and we have a different situation. Even though all logic tells me, “Blair, you are in a pool,” I still am 99% sure that Megalodon has come back from extinction and will be remaking the beginning of Jaws with me any second.

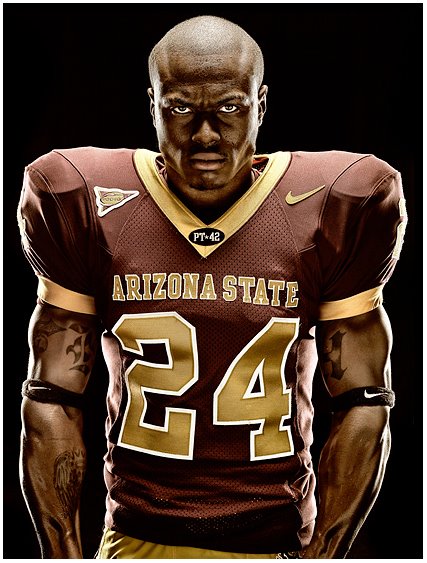

Sharks aside, lighting is much the same way. The eye finds discomfort and intimidation in the unknown, and the unknown is where the light is not. The approach to making a subject intimidating should not be a mass of lights cranked to 11, but a single focus of direction where one light dominates and the remaining support the fear. An example of this that I shot a while back is this portrait of a football player.

As I promised in the beginning, here is the RAW image from the shot to show where we take it on set before it goes into good ole Photoshop.

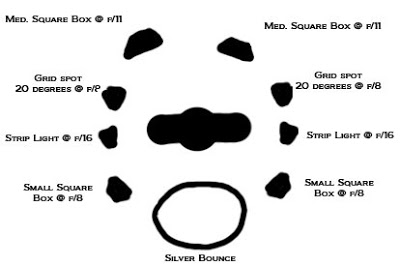

And the lighting scheme: (notice that the powers of the support lights never go above the singular direction of the key, if we broke that rule, the eye would become comfortable)

On the most recent shoot we approached things with the same idea, but incorporated action, so the singular direction source had to be broadened, but still contained. There are many people that approach lighting or even teach the one light approach, which I enjoy for it’s simplicity. However, if I may add an addendum; I think that it should be more of a single direction source approach (doesn’t roll off the tongue as smoothly). Remember, as photographers, we are telling a story, not just telling our viewer that our subject exists.

The final with smoke and plate:

The RAW test before smoke. This shot is actually a prep shot for the main image that involved smoke from a machine (camera left), but shows lining of subject and a disregard for any details that I don’t want my viewers to see:

Believe it or not, one of the most important parts of lighting is the camera, and your knowledge of it. To best light a subject where you want to play dangersouly with shadows, you have to know and trust the sensor that lies at the heart of your camera. I was shooting on a Nikon D3x which lets me shoot more contrast out of camera with the safety that my shadows will exist when I open the file. I only know how far I can stretch the contrast ratio with my camera from practice. There will always be those that measure the heck out of a camera and it’s sensor, but to push one on set with a job on the line is an act of trust in the equipment you are using.

As with the need for consistent sensor performance is the need for consistent lights. For campaigns, I trust Profoto 8’s with my livelihood. The power is always sufficient to close down and delivery is quick enough to avoid blur. From there the rest comes down to build, reliability and standards that make it easy for me to tell an assistant what is needed, even when they speak a different language.

With an approach to technical lighting, and equipment that can deliver you will actually become more financially efficient. In what might take you five minutes on set to put up a light, you will save yourself hours if not days in post trying to create a texture that doesn’t exist because the photo wasn’t lit correctly. As photographers, we should crave perfection and do everything in our ability to create it. These are details that your clients deserve, and that will make you proud of your work.

1 Comment

Comments are closed.

[…] and a Nikon and Maurice Lacroix Ambassador, Blair Bunting sure knows how to light. In a recent blog post, titled How to Light a Football Player, Blair shares some of that […]